Preface

In this post I’ll detail an architectural pattern building on the concepts and principles of the most obvious of inspirators. Some might not approve of my tasty Jambalaya, but I think its has a lot of flavor and gets the job done. It’s a pattern, I’ll also include some guidelines that are more implied than required to this. I’ll start by saying that if you are looking for something revolutionary you’ll be disappointed: it is merely a way to make it easier to adhere to some principles, like most patterns. And I’m ripping off more established practices.

Goals

I’ll describe a model for organizing components based on abstraction levels as well as function, providing a clear and controllable structure for managing dependencies, thus promoting decoupling and cohesion. I want to make it easy or even a natural consequence to adhere to Robert C. Martins “Package Principles”, which I believe to be insanely undervalued compared to the commonplace SOLID principles. I’ll try to describe this model as generic as possible, within the domain of Object-Oriented Design. For the sake of communication I give this pattern the handle “3-Layer Directed Graph Dependency Model”.

Layering

The model prescribes three layers, one of which is a Service Layer as described by Martin Fowler in PoEAA. Fowler did not organize his Service Layer example using levels of conceptual abstraction, this model does. The Domain Model is at the center, similar to Evan’s Domain Driven Design layering proposition. If you find this post interesting, you should probably dust off DDD, as well as PoEAA and Uncle Bob’s handbook. I’m not proposing anything unconventional here, but the dependency model is dependent on these layers, so I’ll detail them anyway.

Terminology: Conceptual Abstraction?

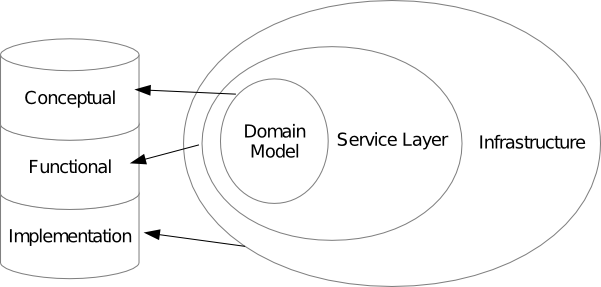

Depiction of layer conceptualisation

What I mean when I refer to conceptual abstraction is the level of commitment to specifics not ubiquitous within a domain, but the inverse. Application layers should reflect this: the more application specific behavior is, the further from the core of the model it should be placed. A way of wording an approximate opposite could be “behavioral specificity”, if that helps.

Domain Model

This is the Domain Model as described by Martin Fowler. Object-oriented in its most obvious form, this layer contains sets of classes that attempt to translate domain specifics to a model of objects and their interaction. Objects in this layer have an identity and are generally long-lived or can be reconstructed / marshallled equal as far as the objects in this layer and its clients are concerned.

Service Layer

For the most part, also as described by Fowler (“thin” variant). The Domain Model defines it’s own interactions, any domain logic does not belong in the Service Layer, implementation details might. Anything in the Service Layer not directly concerned with providing the right input to the right procedures on the the right domain objects is suspect: there is a good chance you’re missing some domain knowledge. The Service Layer is essential in defining what objects should say what to each other in response to an “outside” request, it should not define what Domain Objects say to each other after that.

Infrastructure

This includes anything in the way of an end-client talking directly to the Service Layer, and providing whatever interfaces are needed to do so. It should include all technical and/or UI commitments. I could give you examples, but chances are this encompasses 90% of your coding work, you don’t need them.

Dependencies and Granularity

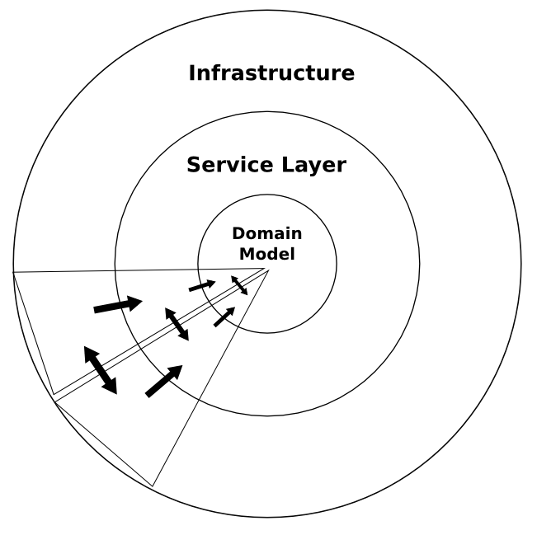

The simplified “slice” model, useful only to illustrate direction of dependencies

If you have used a proper Domain Model with a thin Service Layer before, the layers and my descriptions of their responsibilities probably seem a little obvious. The pattern mostly prescribes them as a precondition, not a unique property. Even if you have successfully applied a similar layering model in the past, the guidelines concerning direction of dependencies might still provide you with some guidance towards maximizing maintainability of larger applications by providing clarity when organizing your components in each layer.

The dependency model has the following absolute rules:

- Code can only depend on code within the same layer or the layer it encapsulates.

- Within the same layer, packages can only depend in one direction, cross dependencies are prohibited (note that the illustration on the right suggests bi-directionality, this is not accurate: the dependency could be either way, but not both ways).

In its simplest (non-realistic) incarnation, the model exhibits pie-slices based on functionality. The unit of re-usability is that of a package; creating “slices” through the prescribed layers based on a conceptual grouping of functionality can provide an easy starting guideline. For example, the concept of authentication could have similarly named packages in each layer. But the model is based on the assumption that when encapsulating behavior in layers stacked by conceptual abstraction, stability in the sense as described by Robert C Martin is or should be mostly parallel to that abstraction, resulting in the visualized (surface) size of layers to be more or less proportional to the potential quantity of re-usable components.

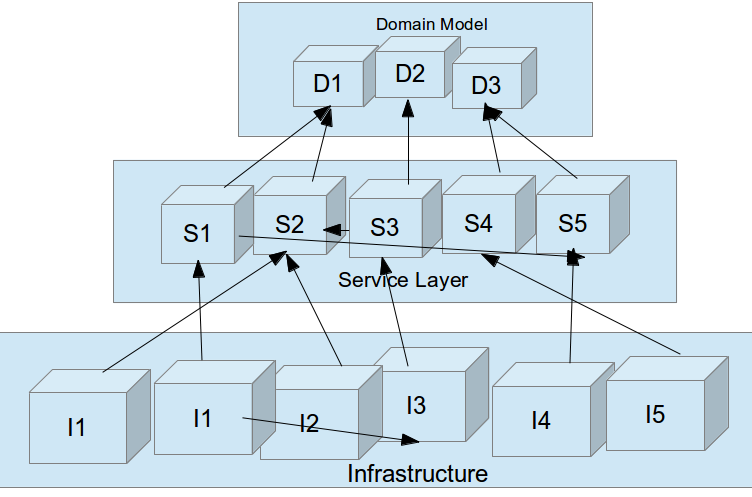

Alternate visualization showing dependency and granularity implications

Similarly, while this model prescribes some granularity purely by imposing the layer model, technically one could organize an application using only a single component per layer. But the proposed relation between stability and conceptual abstraction implies that the potential quantity of reusable units within a layer is smaller relative to the negative of its distance to the models outer boundaries (as implied by the statement that illustrated surface area is more or less proportional). Simply put, more independent infrastructure components could provide external interfaces to a single service layer component, and a single piece of the domain could be used by multiple components in the Service Layer.

Aside example: Say we’re building a consumer-facing application for a company with an existing customer base. The function of authentication demonstrates the point in a familiar domain: the domain model will need at least an entity that models someone or something that needs to be granted access. I don’t think it’s a stretch to assume that more than one Service will need this package, and probably even more Infrastructure packages will need these Services. It would be semantically and conceptually objectionable to put it in any package in the Domain Model semantically coupled to authentication.

Beyond these implications, the model does not actually prescribe any granularity within layers. Though I should stress a guideline which effects granularity: you should avoid depending on more than one packageoutside the layer. Depending on more than a single package in the layer above it is a pretty clear sign the package is “doing too much”, or more formally, violates the SRP on a package level. The last illustration depicts an example of proper dependencies: not only do packages depend on a single package one level up, dependencies within a layer are limited to siblings that do not depend on the same higher level packages as the package itself. Because when packages in the same layer depend on the same higher level package and there is also a dependency between them, in other words when you’ve created a “dependency triangle”, it is implied that the division is redundant and the two packages can be merged. Assuming packages higher up in the hierarchy can not be split by concern, which should be preferred.

Wrapping Up

That’s it, thanks for reading.